Mary Katherine Goddard became the most 'un-famous-famous' female publisher when, in January, 1777, she printed the first copy of the Declaration of Independence that included the names of every signatory. But Mary’s journey to her place as a premier publisher during the American Revolution was a lifelong process that began with the passions and education provided by her parents.

Mary was born in Connecticut in 1738 to Sarah Updike and Dr. Giles Goddard. Her mother, Sarah, was raised by a wealthy family in Rhode Island, and she taught her daughter to read and write. Mary later attended public school in New London to learn languages, math, and science. Her only surviving sibling was William Goddard, born 1740, with whom she spent her life working in the publishing and postal industries. Both children were educated according to their parent’s interest in the printing and newly established postal system; their father, Giles Goddard, was a postmaster and physician. This education informed their life’s work.

Over the course of their lives, Mary and Sarah ran several print shops and bookstores. Though they were often in partnership with William, much of their time was spent bailing him out of his business mishaps. Described as having a ‘choleric disposition’ and ‘hot temper,’ William was not a sound business partner, despite having trained as a printer’s apprentice in New Haven while working on the Connecticut Gazette in 1775. Early in William’s career, Sarah invested money into William’s publishing passions, and by doing so she established the first printing press in Providence, Rhode Island. Following this, Mary and Sarah moved to Providence to work with William in the shop, printing the Providence Gazette and Country Journal, in addition to almanacs.

The Goddards were a political family, and they printed papers voicing strong opinions against the British crown and its policies. After three years at the paper, William moved to Philadelphia while Sarah and Mary kept the Providence newspaper running through 1768. The press became known as ‘Sarah Goddard and Company,’ with the ‘company’ referring to Mary. In addition to the press, Sarah adopted her son’s responsibility as postmaster when he left the state. According to William Goddard’s biographer, “the shop [became] one of the largest in all the colonies” after passing into Sarah’s hands.

While Mary and Sarah were in Rhode Island, William founded the Pennsylvania Chronicle and Universal Advertiser in 1776 with new partners. Over time, the partnership proved fraught as his new colleagues disagreed with his political views and his desire to express them in the paper. Though Sarah and Mary both had strong political views, they urged William not to be so strident in using the press to voice his private opinions. William’s partners urged Sarah and Mary to leave Rhode Island and to join William in Pennsylvania where they might be able to exert their influence, which they ultimately agreed to do.

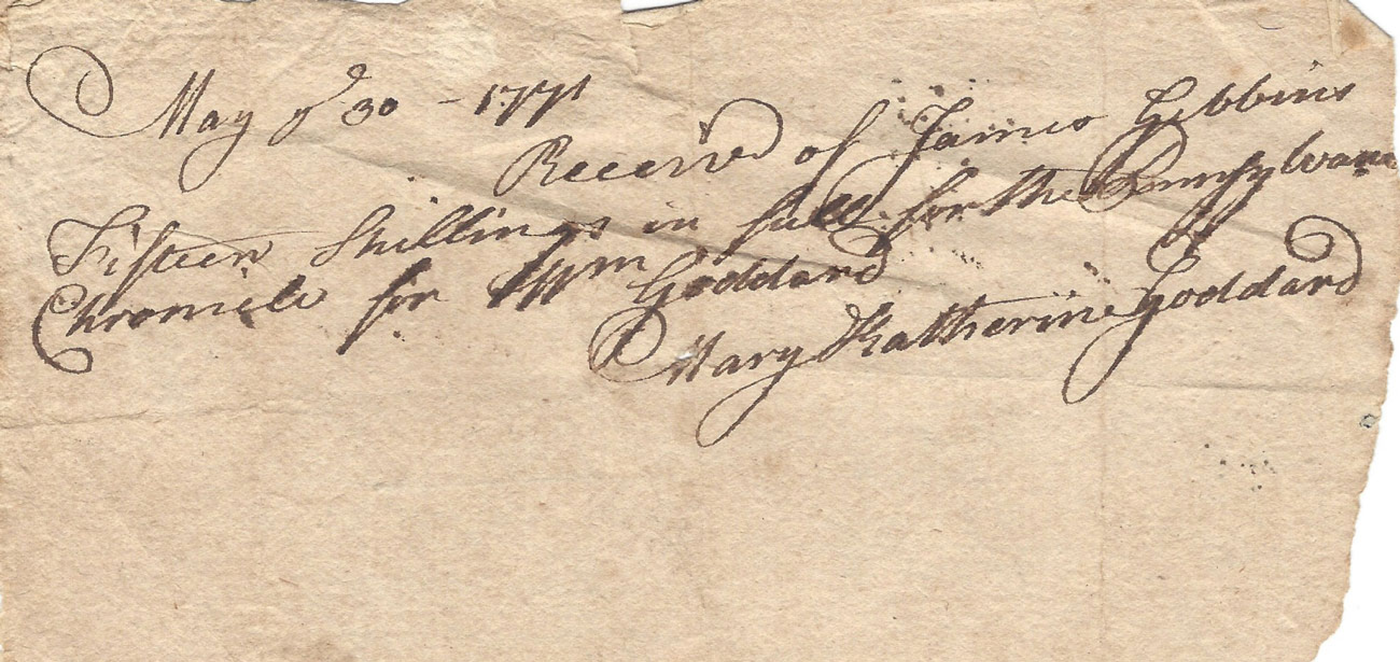

The move to Philadelphia was not an easy transition. Conflict continued between William and his partners, and Sarah and Mary were left again to run William’s press on their own, this time the Pennsylvania Chronicle and Gazette, improving subscription numbers as they did so. In 1770, when William was away in New York, Sarah died. Mary was thirty-two years old, and she continued to run the newspaper until the following February when the Philadelphia Chronicle was forced to close due to William’s 1771 debt imprisonment and the Crown Post’s refusal to distribute their paper in the mail.

As pre-revolutionary tensions grew between the British and Americans, printers began to take political sides in their publications. The Goddards were sympathetic to the revolutionary cause and were watched closely by the Crown. Eventually, they had to use private carriers to deliver news past the prying eyes of the English Crown postal office.

The situation spurred William to create an American postal system, one founded upon the principles of “open communication and no governmental interference.” On September 29, 1774, William petitioned the Continental Congress to form a new postal system that would protect the rights of free exchange of information. The new system was in direct competition with the existing British-run mail. On July 16, 1775, the new revolutionary postal system, known as the ‘Constitutional Post,’ was established, ensuring readers were informed of events during the American Revolution. Six months later, it forced the Crown Post out of business. The Goddards’ creation became the foundation of the United States postal system.

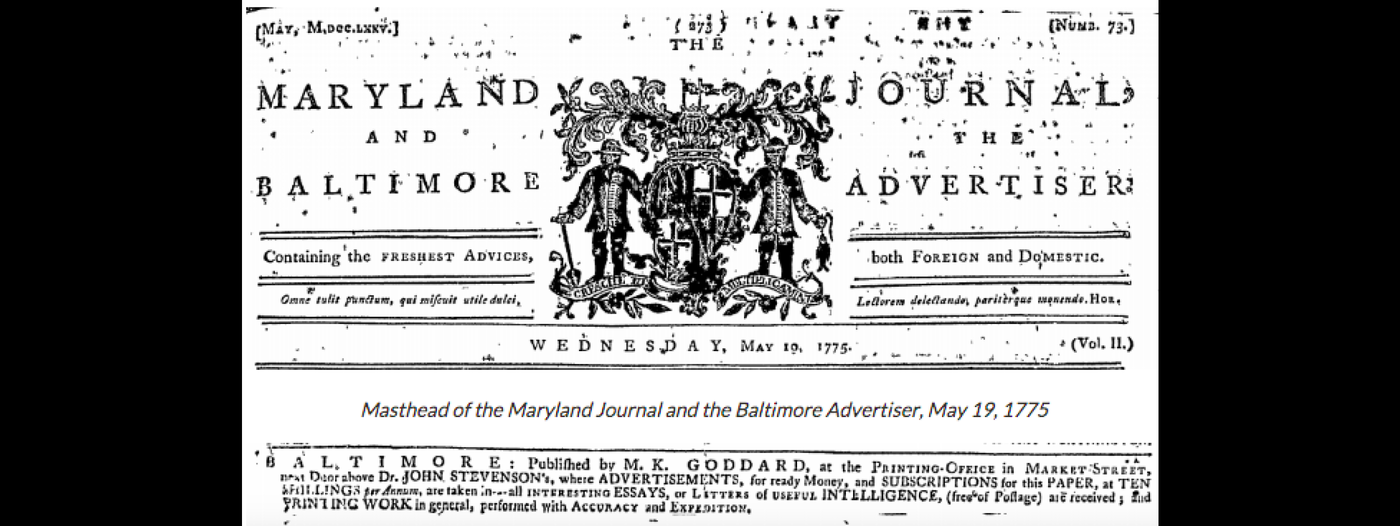

During this time, Mary left Philadelphia and moved to Baltimore where she and her brother jointly published the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, which was the first newspaper in that city. Eighteenth century newspapers were crucial during the revolution, exerting great influence on opinions concerning British rule. Though a passionate patriot, William continued to be an unreliable figure. He printed contentious articles in the paper and was often in trouble with the law. In the end, once again, he left Mary to publish alone.

1775 was a turning point in Mary’s career. In the May 10, 1775 issue of the Maryland Journal, Mary became the first woman in America to print her name as publisher of a newspaper, using the gender-neutral identity ‘M.K. Goddard.’ She later added bookbindery to her business, printing almanacs, pamphlets, and the occasional book. That same year, Benjamin Franklin was elected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress and appointed PostMaster General, a position he had held under the British Crown. On July 26,1775, Franklin appointed Mary as the first, and only, female Postmaster in America. Mary’s dual position as postmaster and publisher in Baltimore, a major port city, provided her enormous influence, which she used to promote the patriot cause.

Mary’s Maryland Journal was one of the first newspapers to report the battles at Lexington and Concord, battles that started the Revolution.

She also reported on the British blockade of Boston Harbour, and officially endorsed the Homespun movement, which supported Colonial rather than British made goods. In addition, Mary later published Thomas Paine’s “The American CRISIS, No. III. By the Author of COMMON SENSE” on the front page of her May 10, 1777 edition of the Maryland Journal. The series consisted of thirteen articles written by Paine during the Revolutionary War advocating for independence from Britain. Mary was willing to take risks and publish political perspectives that declared the quest for freedom from the Crown. Her fiery editorials frequently set the tone for pivotal moments in the Revolution.

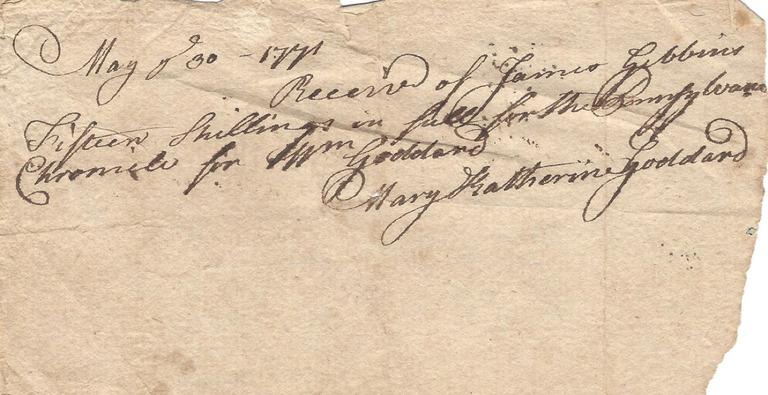

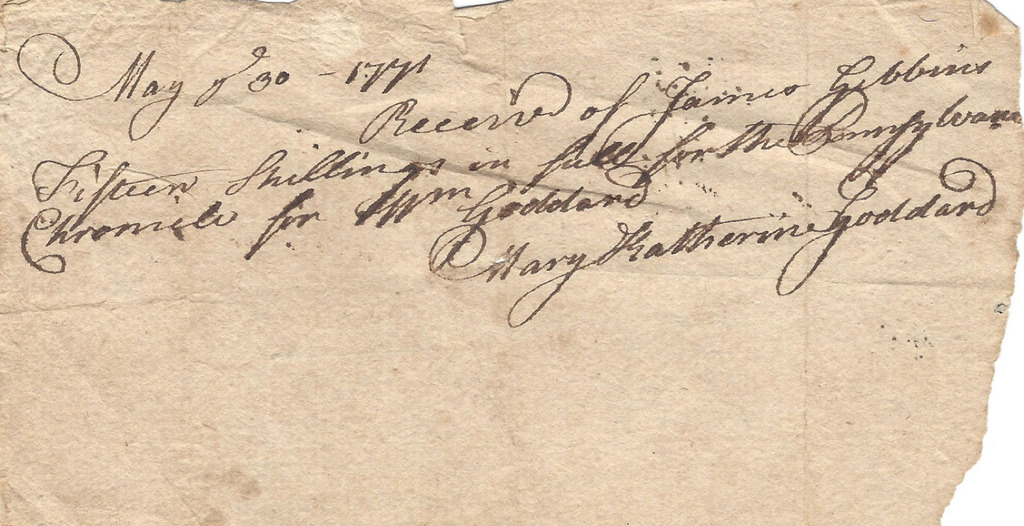

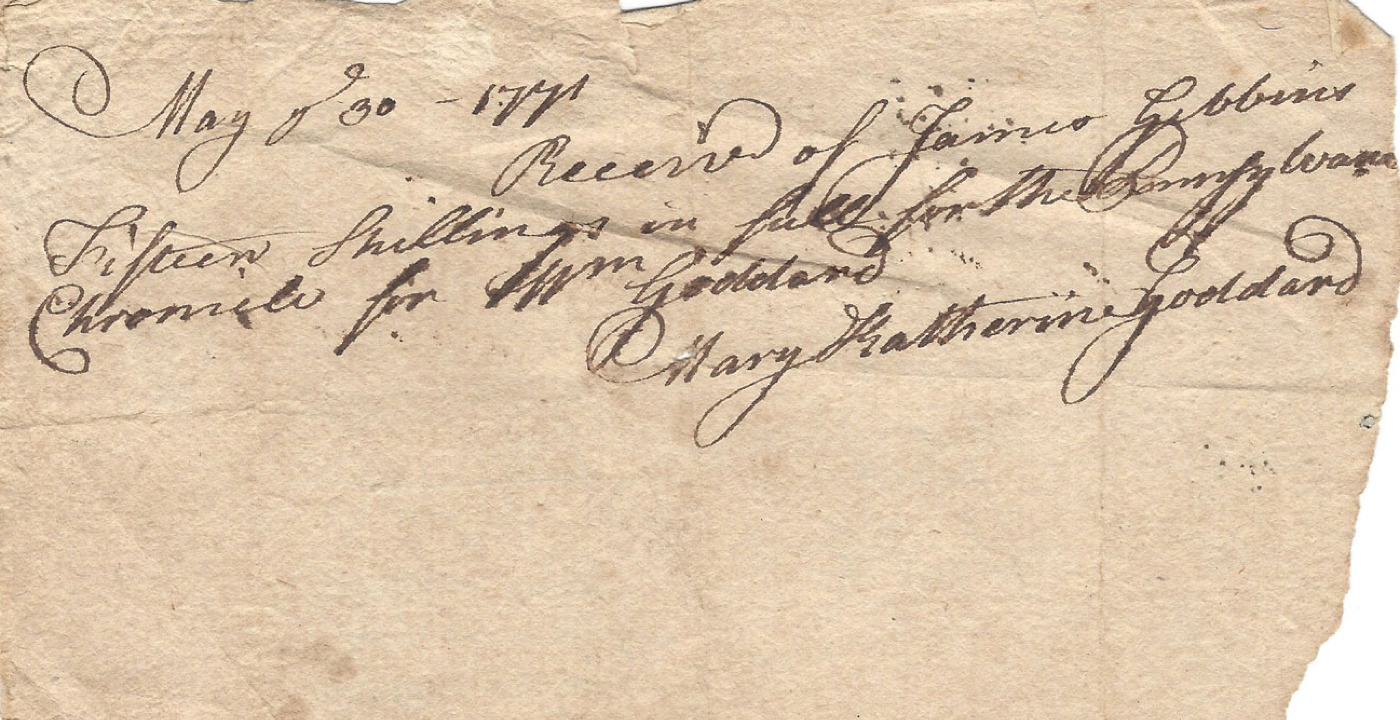

The Revolutionary War, though, created a paper shortage for publishers. The war also sparked inflation, leaving subscribers with little cash. To keep her newspaper publishing regularly, Mary accepted barter in beef, pork, animal food, butter, hog’s lard, tallow, beeswax, flour, wheat, rye, corn, beans, and other goods she could either use or sell in her shop. During the financially lean years of the Revolution, Mary ran the busy and crucial Baltimore Post Office as well as a bookstore, print shop, and newspaper.

When American independence was declared from the British in July 1776, copies of the Declaration of Independence were printed and circulated without signatures becuase any signer would have been executed for treason were their identities known. Six months later, in January 1777, recognizing the excellence of her newspaper, the Continental Congress asked Mary Goddard to publish the first copy of the Declaration of Independence with all the signatories listed. In a show of unwavering strength, Goddard printed her full name at the bottom of all copies distributed to the colonies. Though other copies of the declaration were printed, hers alone presented the names of every signatory. Goddard’s edition changed everything. In printing the names of the founders, Mary made the Declaration all the more devastating and remarkable.

Unfortunately, Goddard’s career quickly declined once American independence was secured. Her experience exemplifies the gradual decline of the status of American women after the Revolution. In 1789 the National Post Office took over from the Constitutional Post and its first Postmaster General, Samuel Osgood, decreed that the head of the Baltimore postal system must be a man. In response, Mary, who had been the postmaster for fourteen years, appealed to President George Washington and petitions were sent in her favor from over two hundred prominent Baltimore merchants and residents. They received no reply.

Mary died in Baltimore in August, 1816, leaving all her personal possessions and property to her African American servant Belinda Starling, and releasing her from slavery.

‘The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I.’

— Thomas Jefferson

Christine Moog is a book designer specializing in monographs and catalogues on art and architecture. She received an M.F.A. in graphic design from Yale University and an M.A. in art history from the University of Toronto. An Associate Professor at Parsons School for Design, she has previously taught at Yale University, the School of Visual Arts, the City College of New York, and Ontario University of Art and Design. She is the author of “Women and Widows: Invisible Printers,” in Making Impressions: Women in Printing and Publishing, with The Legacy Press, and the forthcoming “Women, Printing, and Prosecution,” in Printing History and Culture, Volume Two, with Peter Lang Publishers.