Several weeks ago, I read an article in the New York Times celebrating the 20th anniversary of the film Legally Blonde. Calling it a “feminist masterpiece,” the writer interviewed several people connected with the movie—actors, cinematographer, screenwriter, casting director, costume designer, and so on—all of whom weighed in on the film’s importance and relevance. Toni Basil, the choreographer, remarked: “Women, equal pay and the #MeToo movement, so much has come around in the last 20 years that did not exist when these girls were creating this movie.”

I’ll leave to one side Basil’s reference to the women involved in the film as “girls,” and focus instead on the claims that 20 years ago, women were not demanding equal pay for equal work, and that prior to the #MeToo movement, women were not trying to hold men to account for their sexual behavior. Are these statements true? Of course not! Women have been seeking equal pay for equal work for decades. And they have been lambasting men for their sexual misconduct for—and this is not hyperbole—centuries. In every age, in every generation, in some way or other, women have been demanding a seat at the table. And every time they do, an odd sort of cultural memory lapse becomes apparent: it is as if women were making that particular demand for the very first time. But it isn’t the first time; it’s the thousandth time. Why are women’s pleas for justice, for equality, for fair treatment, for access to the goods of life—especially goods related to knowledge-seeking—met with such massive cultural forgetting?

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which denies women a Constitutional right to abortion, is a case in point. Do women really have to beg, plead, and argue again for control over our own bodies? Sadly, yes.

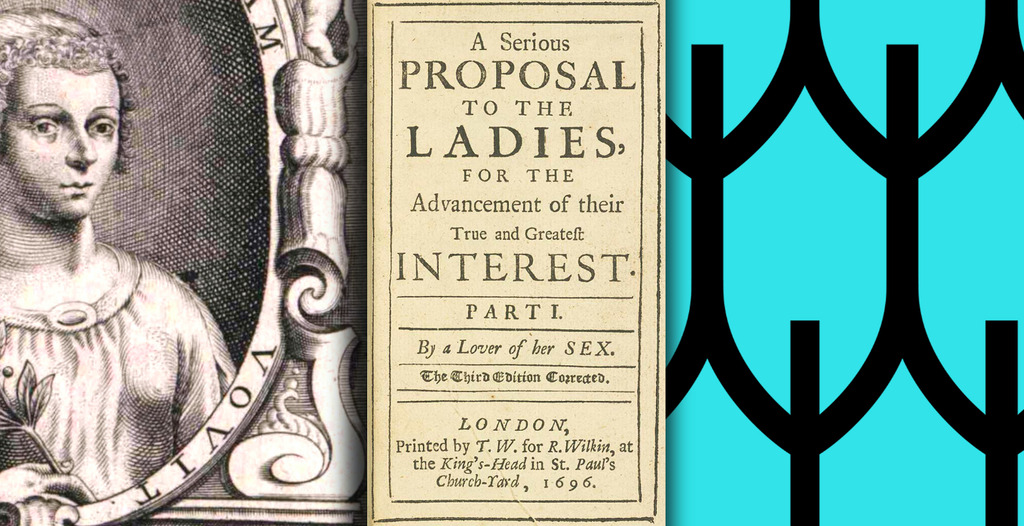

It is not only women’s pleas for political goods that have gone unheeded; so too have our pleas for epistemic goods. When I was in graduate school, I “learned” that there were no women in the history of philosophy. When I became a professor of philosophy and did some investigating – both within my discipline and outside of it – I learned that there were scores of women in the early modern period, and even earlier, who were writing philosophical works, and that many of these thinkers were writing explicitly feminist texts. How exciting it was to discover such works from the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries: Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies; Lucrezia Marinella’s The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men; Marie le Jars de Gournay’s Apology for the Woman Writing; Mary Astell’s Some Reflections Upon Marriage, and many, many others – much too numerous to list. Of course, understanding these thinkers as feminist required a broadening of that concept to include works that argued not for women’s rights (there was no concept of natural rights before the 17th century) but for equal access, especially to education. Still, my excitement at the realization that feminism had been around for a long time turned into a perplexed dismay when I began to wonder why it was that women had been making the same arguments not only day after day, week after week, month after month, and year after year, but century after century, and, incredibly, even for a couple of millennia. Why are women’s demands so thoroughly unheeded?

The New Historia is a profoundly important undertaking because it places that question at the center of its work. It exposes the historical misogyny that has resulted in a feminine abyss – that is, the complete absence of women’s intellectual legacy from cultural memory at any given moment. The New Historia is not simply engaged in a historical recovery of women’s work; rather, it insists on a new knowledge-ordering system that embeds women’s contributions to intellectual, literary, political, and artistic life into the cultural consciousness with the aim of ending the cycle of forgetting and recovering. The New Historia makes female invisibility visible; it connects the dots and creates the conditions for massive cultural remembering.

Nancy Kendrick is professor of philosophy at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, and The New Historia Philosopher-in-Residence. She works on women writers of the Early Modern period and has published articles on the philosophy of Mary Astell, Mary Wollstonecraft, and others. She is currently at work on Unheeded: Epistemic Harms Against Women, Then and Now, coauthored with Jessica Gordon-Roth, associate professor of philosophy at the University of Minnesota.